Meet Mr Frequent Failure

What talent management and leadership should know about that employee who embraces failure as a source of pride

Corporate America offers some fascinating wildlife that you seldom see in the world of entrepreneurship and results-oriented work. In the Meet Mr Series, we meet some of these corporate creatures and their challenges for talent management. One misguided creature who can add unnecessary costs in corporate America is Mr Frequent Failure. Mr Frequent Failure embraces his failures as badges of honor and leads his team into one failed idea after another.

But first, a fictional story. Because I'm creating a fictional stories as examples in this series, I'll call Mr Frequent Failure in my story Frank. As a reminder, our fictional company is ABCZ Corporation.

Story

David walked into the office and Frank and Anne stood to shake his hand. "Welcome David," Frank started. "We were very impressed when we looked at your resume. We think you might make a great addition to our team." Frank pointed to Anne, "This is Anne, who is the director over our team and she had a moment in the office today and wanted to meet you."

"Hello David," Anne said shaking David's hand. "Frank is seldom impressed with any candidate, so when he was bragging about you the other day, I had to meet you." David smiled and nodded, "I also have to warn you that Frank is one of our smartest employees, so be careful about arguing with him because he tends to know what he's talking about as he's seen our organization grow." Frank showed a huge smile on his face with pride and Anne walked to the door, "I have to be going as the board wants us to discuss why we sent clients the wrong data yesterday."

"It was great meeting you," David said as Anne left. Once she left, David turned to Frank, "What happened yesterday."

"Let's just say that yesterday was a great opportunity to learn from failure," Frank started. "Our clients send us claims data daily and we have processes that validate these claims and return decisions." Frank motioned David to sit in a chair within the office as he sat down in another chair, "I won't say that it's always worked beautifully because we've had some issues that made great learning lessons, but we have automation built around it now so we don't have to worry about it as much. Anyway, yesterday a client sent us their claims information but they messed up the input on some of their claim which our system read as another client's claims. The result was that one of our clients didn't get decisions on a batch of claims while another client got decisions claims that they didn't have, which created confusion on their end." Frank shook his head, "They thought the false claims were legit and were mixed up so they sent them out." He paused while laughing, "Can you believe it?"

David nodded slowly, "So one of your clients sent a batch of claims, but had identified them incorrectly and the other client ended up getting decisions on this batch of claims but the batch wasn't their claims, even though they treated them as such?"

"Exactly, crazy right?" Frank agreed. "I never imagined that could even happen! Such a crazy moment. But it made a great opportunity to learn - clients can mix up their claims!"

"When you receive claims, how do you identify them by client to ensure there's no mix-up?" David asked.

"Well, we've never had a need to do that," Frank replied quickly and continued, "Our clients have always used their own way to uniquely identify their claims. Most of them either have a set format for their length or start with leading alphanumeric characters. That's always been good enough for us and since we use the same architecture for processing decisions on claims, there's never been a need to delineate client batches." Frank paused while smiling and lightly laughing, "Just the thought of a client suddenly sending us a batch of claims with the incorrect information is crazy. I never thought I'd see it!"

The interview continued for an hour and as it continued, David observed that Frank enjoyed feeling as if he was right. David had noted that highly technical people such as Frank generally liked arguing about minutia because technical people needed to know exact details, even if there's a difference between important details and trivial details. David observed how Frank would speak about changing his approach after a failure, not considering how he was approaching challenges before a failure. For instance, when Frank and David were talking about the overall architecture for clients pushing their claims to the company, David asked Frank how he knew everything was functioning correctly. "What do you mean?" Frank asked.

"How do you measure that you're efficiently receiving the information that you should - such as a client pushes a million claims to you and you received the million claims?" David asked.

"It's not like that because we don't need it like that," Frank argued. "We have architecture that receives the information the clients send us; we don't need to worry about tracking the amount because we have sufficient architecture to receive as much as they send. Gosh, I can't even imagine the waste of time creating reports or such showing clients how many of their records they received. Talk about a waste! Plus, if there was an issue, we could discuss with our clients about receiving records - they probably pushed them incorrect to us or something. We've never had that issue."

David realized that Frank approached problems with the attitude of "It will work and if it doesn't, we can learn after we fail." When the interview finished, Frank invited David to come in the next day over lunch to see the team in action solving a problem and David agreed.

The next day, David walked into the company and asked for Frank. The receptionist told him to wait in the foyer as he went to get Frank for David. David nodded and walked around the foyer looking through the glass windows of the people bustling on the sidewalk by the street. As he looked around at everyone, he saw as two people rushed through the doors of the building and happened to hear one of them mention Frank's name - "Frank can't believe that it failed last night, it's always worked. Gosh, this is turning out to be a mess." The two people rushed into the office area of the building and the receptionist returned with Frank, who looked stressed.

"David, good to see you again," Frank said offering his hand for David to shake. "We are in a messy situation right now, so I'm not going to be able to grab that lunch." He paused while looking at his watch, "I'd love to show you around, but I have a war room call in ten minutes because we're facing a big issue right now."

"If you don't mind me asking, what's going on?" David asked.

"Long story short, our entire architecture that receives client claims went down last night," Frank answered. "One of our data centers lost power because of an area blackout, but we built our infrastructure to have no single point of failure. What we didn't realize was the other data centers couldn't handle the volume, so one of them became overwhelmed and froze. The other three ended up getting backlogged with claims." He scratches his head. "I've never seen anything like this, but we ended up processing very few claims last night and now we're behind. Our clients are extremely angry." Frank looked at his watch again, "Anyway, I've love to talk and have lunch, but we're overwhelmed at the moment. Someday, we'll look back on this and laugh, but we got to learn from our failure today."

"Yeah definitely do what you need to do to solve your issues."

"Thanks and I wish we had someone else to show you around," Frank said. "But right now, everyone has full attention to this, so we have to solve it first. I'll reach out to you when finished as you can see, we're going to need your help."

What the Research Shows

Talent management may note over time that Mr Frequent Failure embraces failure to a degree that he doesn't seem bothered by his failures almost as if his failures are his goal. In the book Psycho-Cybernetics, Dr Maltz highlights how we have mental patterns of success and failure. When we're facing failure, this gives us time to reflect about our mental pattern. We can compare how we were thinking and what we were doing when we were succeeding versus when we were failing. The idea here is that we don't look at failure as a positive or even as a necessary event, but as a warning sign that we're doing something incorrect. Embracing failure doesn't mean that we praise failure - we should never start something with the intent of failure.

While we shouldn't fear failure, we should be aware that failure comes with significant costs. As I've continued to study how Millennials and iGenZ behave, one re-occurring pattern I've seen with both generations is "What's the worst that could happen?" This attitude toward failure - as if it's no big deal - actually misses the reality that failure can come with huge costs over time. This is especially true if you’re the other person in the situation (ie: a client) paying for the costs!

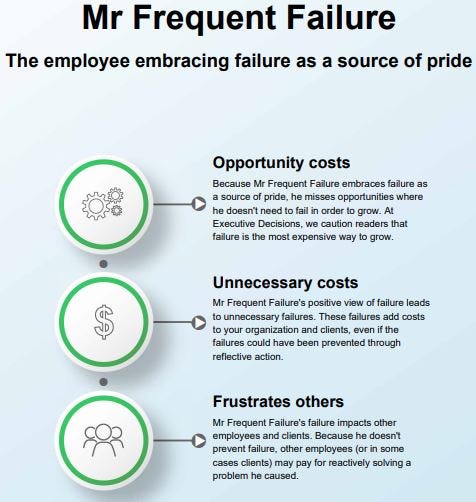

If you're in talent management, my first observation may sound extremely contrarian as we are told the opposite. Yet a person who lacks a fear of failure may engage in reckless behavior that could bankrupt a company. We can see in the story that Frank does not fear failure nor does he take steps to prevent it. David asks Frank some key questions that show that David is thinking about how the company is taking steps to prevent failures. But since Frank has a positive view of learning from failure, he doesn't fear failure - he'll just learn! The problem that we see in the story is how this attitude ends up causing issues for clients. Frank may feel positive about failing so he can learn, but does a client feel positive about not getting a response to important claims? We'll even note that when David goes to meet Frank for lunch, Frank has to cancel due to an emergency. Consider how Frank's approach has even cost David (not a client) because he learns from failure rather than preventing failure.

You'll sometimes hear people say in talent management that you can only learn from failure, not success. I don't agree. What we see in this story is that prevention is much more cost efficient than learning after failure. We'll note in our story that Frank doesn't care about preventing problems because he has embraced failure. If a process fails, his attitude is "Well, I'll learn from it." By contrast, a person who fears failure will do what it takes to prevent the failure or identify if it may be happening before it becomes an issue. For an example, early in our story we see David asking Frank about how they identify claims from one client versus another client. Frank's answer reflects a dismissive attitude toward preventing failure; it's only after the failure that Frank considers it. Prevention is extremely inexpensive relative to cure and Frank's approach is one of cure.

As I once heard at a human capital event, "If someone has to fail so that they grow, then we don't want that person as an employee because failure can be the most expensive way to grow." You can think of any number of businesses processes where a person failing over and over again would lead to a disaster for your company. When we zoom out in the context of failure, we recognize that while we shouldn't embrace failure, we should reflect on our failures so that we avoid them in the future.

Costs

The first cost with Mr Frequent Failure is that he doesn't evaluate the immediate impact of his dismissive attitude toward failure. For an example, some of the costs to learning after failure are the following:

Negative impacts to clients and (or) other employees

Significant loss of time and energy

Opportunity costs

From a simple time and energy savings' perspective, it is much more efficient to prevent failure than to learn from it, as the latter costs much more than the former. But those aren't the only costs of repeated failure, those are solely the costs to learning after failure. The other costs to failing over and over are also:

Unless there's honest reflection, you actually don't learn from failure

Repeated failures can actually impact how you see yourself over time

Repeated failures can impact how well an organization operates

This is why talent management must be careful with Mr Frequent Failure. He's not only impacting himself and his team in negative ways, he may be impacting the company in negative ways. Unlike some corporate creatures, he needs to be managed appropriately, not shown the door.

The Meet Mr Series

For more in the Meet Mr Series of posts, check out Executive Decisions’ regular Series page. Some highlighted posts from this series:

All images are either sourced from Pixabay or generated. All written content is copyright, all rights reserved. None of the content may be shared with any artificial intelligence.

I never subscribed to the encouragement of killing projects and failing. Think through the problem up front and design things correctly, rather than endless trial and error.